[ad_1]

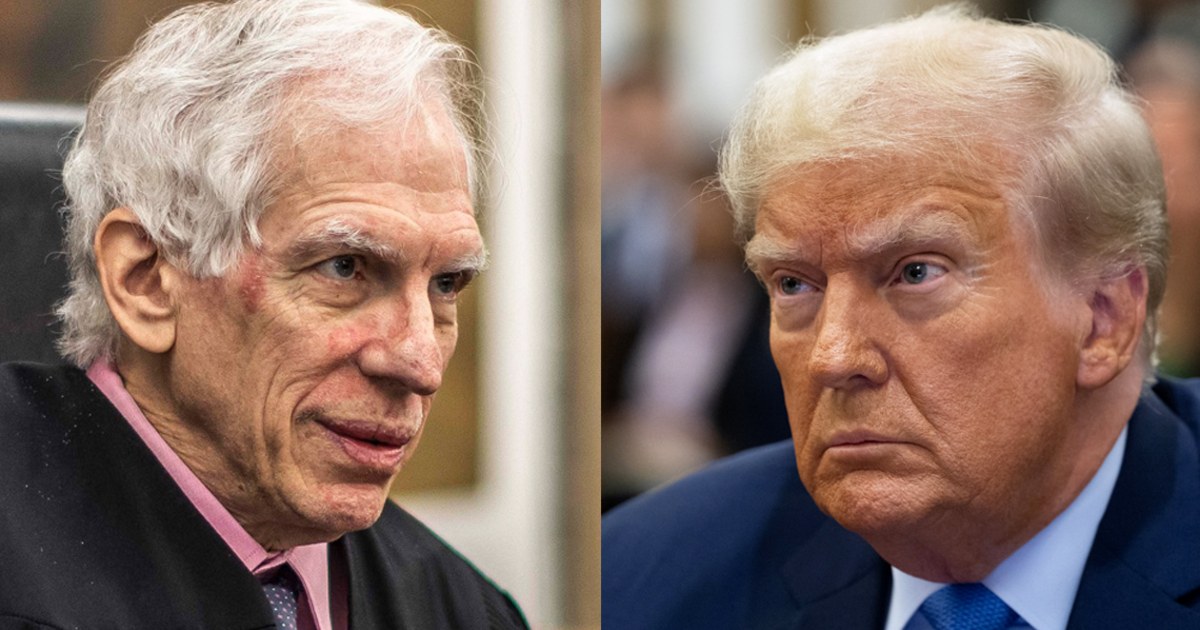

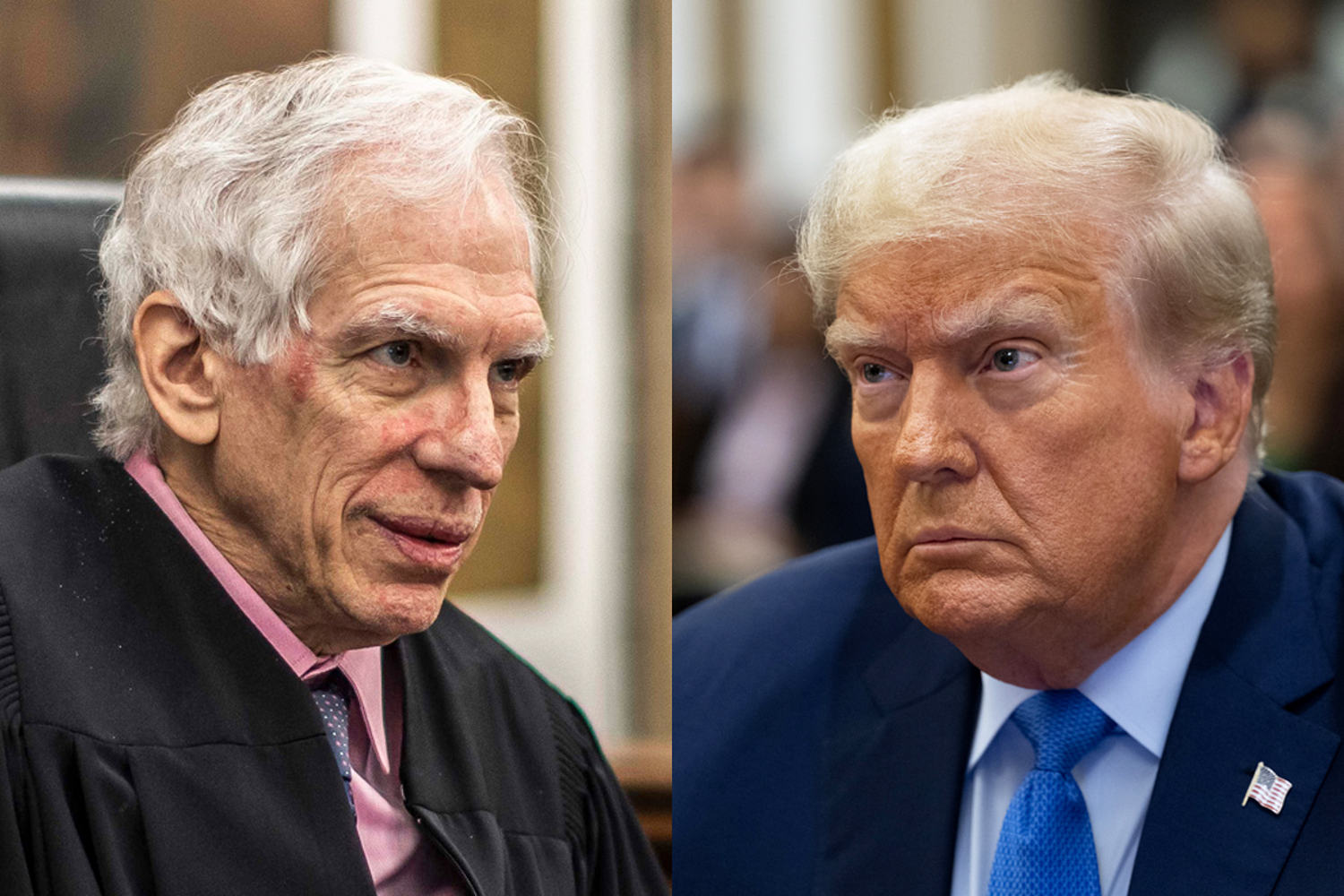

Former President Donald Trump and his legal team have turned New York Attorney General Letitia James’ $250 million civil fraud lawsuit into a spectacle, goading Judge Arthur Engoron, politicizing the proceedings, and spectacularly undermining norms of trial behavior.

That pattern continued on Wednesday, when Trump’s lawyers filed a motion for a mistrial that claimed Engoron’s handling of the trial has been tainted by political bias. (Engoron denied the motion on Friday afternoon.)

Trump’s strategy bears a resemblance to tactics employed by the defendants in the notorious ‘Chicago Seven’ criminal trial more than 50 years ago.

Trump’s strategy bears a resemblance to tactics employed by the defendants in the notorious “Chicago Seven” criminal trial more than 50 years ago, which resulted in the jury convictions being overturned on appeal.

Whether intentional or coincidental, the similarities between these trial strategies are informative — especially for Engoron.

When legal defense teams push and taunt their presiding judges, they are often hoping to make the judge overreact and make mistakes. If judges do take this bait and make errors, an appellate court could potentially conclude that the trial was unfair and reverse the judgment.

The four-month Chicago trial, which took place between 1969 and 1970, was chaotic and political. Eight defendants were originally charged with violating the Federal Anti-Riot Act, 18 U.S.C. 2101, along with additional crimes in connection with violent encounters between Chicago police and demonstrators protesting the Democratic National Convention in August 1968.

A mistrial was declared for defendant Bobby Seale, whom the judge had ordered bound and gagged in the courtroom for a portion of the trial (he was convicted of multiple charges of contempt of court). Two others were acquitted on all charges, and the remaining five were acquitted on some charges but found guilty of violating the Anti-Riot Act.

In New York, Engoron has used strident language in rejecting Trump’s legal positions, terming them ‘pure sophistry,’ ‘risible,’ ‘bogus arguments’ and ‘egregious.’

The appeals court, in reversing those five Anti-Riot Act convictions, noted that the courtroom was often in an “uproar,” and criticized the “provocative, sometimes insulting, language and activity by several defendants.” But, the court noted, such bad behavior did not excuse errors by the trial judge. “There are high standards for the conduct of judges and prosecutors, and impropriety by persons before the court does not give license to depart from those standards,” reads the decision, which notes that the “district judge’s deprecatory and often antagonistic attitude toward the defense is evident in the record from the very beginning.”

In New York, Engoron has used strident language in rejecting Trump’s legal positions, terming them “pure sophistry,” “risible,” “bogus arguments” and “egregious” in his summary judgment opinion. He sanctioned five Trump attorneys $7,500 each for the “borderline frivolous” arguments in their briefs.

Harsh language isn’t a problem if it’s justified. But the more Engoron pushes the envelope, the more he risks an appellate court disagreeing with his assessment. And Trump’s lawyers can and will argue the judge’s rhetoric is evidence of judicial bias.

And Engoron has already been reversed by the New York appellate court, which ruled that the judge should have dismissed Ivanka Trump as a defendant due to the statute of limitations.

Engoron’s interactions with his law clerk, and the drama that has surrounded them, are another area of concern. Trump has repeatedly criticized the clerk, making false statements about her that the court found had precipitated threats of violence. When Trump twice violated a gag order prohibiting such remarks, he was fined $15,000.

The presence of law clerks at all levels of the federal and state judiciaries is ubiquitous. Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, for example, have four law clerks each. Engoron having a law clerk to assist him is commonplace. Less common is a law clerk who sits next to the judge, repeatedly exchanging notes.

When challenged that the clerk was acting as co-judge and creating an appearance of bias, Engoron was defiant: “I am 1,000% convinced that you don’t have any right or reason to complain about my confidential communications,” Engoron said.

Courts have ruled that the communications between a law clerk and a judge are immune from disclosure. But ironically that secrecy could bolster Trump’s argument on appeal, since the content of the notes cannot be examined to determine if the messages were proper.

Engoron’s issuance of gag orders barring Trump and his lawyers from commenting about his law clerk both publicly and in court sessions is also facing scrutiny by a higher court. On Thursday, a New York appellate judge temporarily halted Engoron’s gag orders, citing First Amendment protections. An appellate court panel is scheduled to evaluate the issue on Nov. 27.

So here again we have Engoron committing a potentially unnecessary unforced error. Instead of trying to mitigate risk, he is clearly allowing emotion to color his responses.

And there are other examples of Engoron seemingly overreacting in response to relentless complaining from Trump’s lawyers.

Obviously, Trump’s civil trial is very different from the Chicago Seven trial, a criminal proceeding with a jury, in multiple important ways. And the appeals court cited multiple reasons to reverse the Chicago convictions.

But Engoron would be wise to consider the lessons of that case nonetheless. He needs to take all necessary steps to ensure that a New York appellate court cannot overturn his decision. And that means not reacting to Trump’s hate-filled speech, or to his lawyers’ baiting and provocation. It’s simply not worth it.

[ad_2]

Source link