[ad_1]

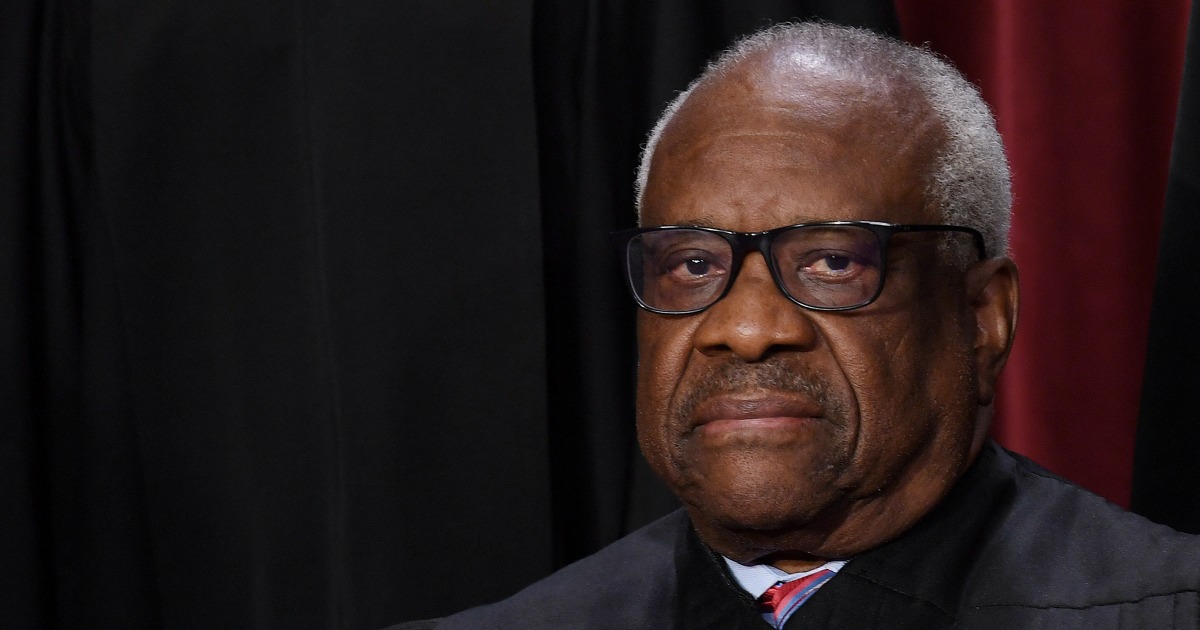

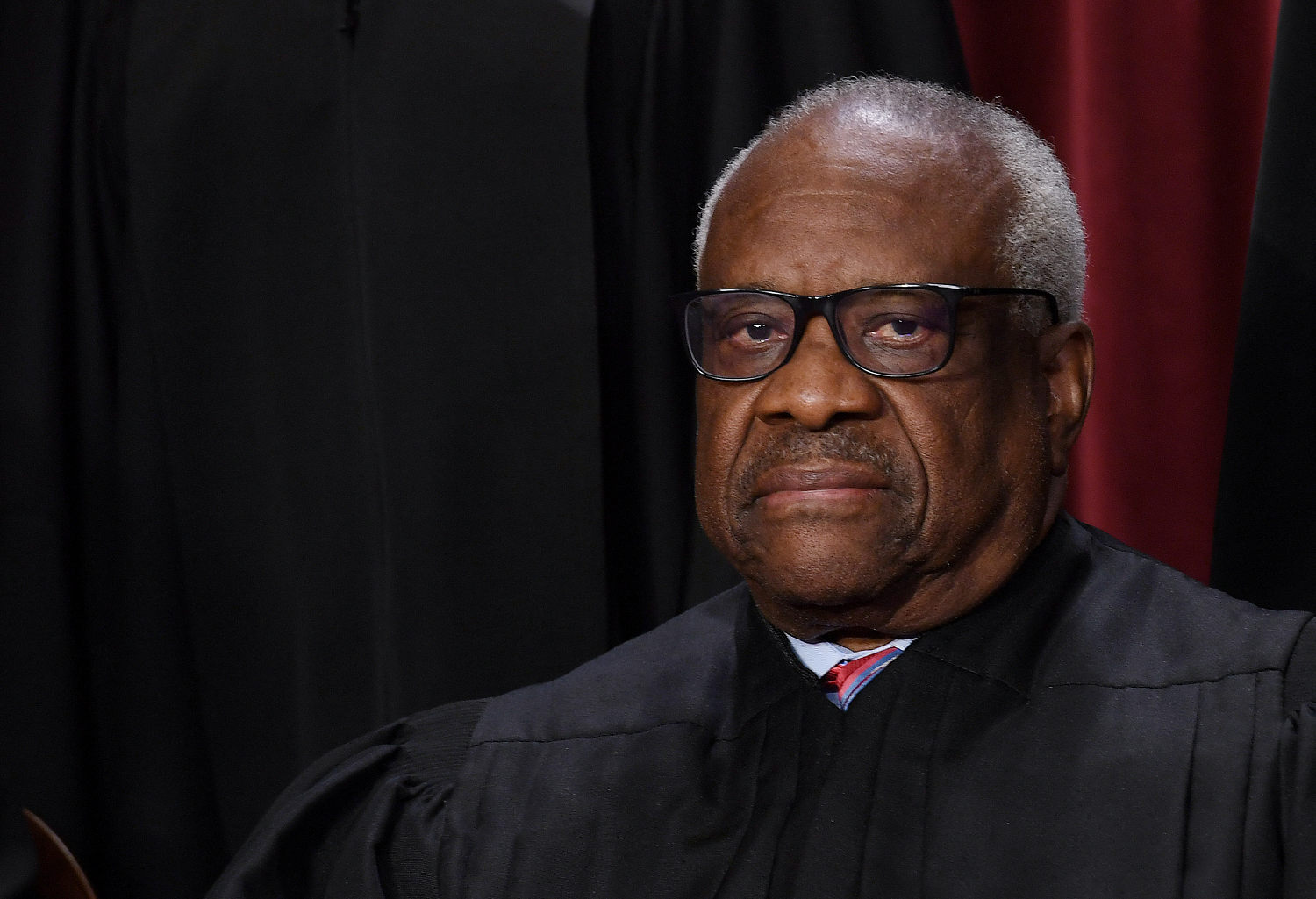

The Supreme Court is facing a momentous term for our democracy— one like few others in its storied history. The cases they will review arising from former President Donald Trump’s attempts to cling to power pose a profound test, including for the court’s new ethics code. Under that new code, it’s clear that Justice Clarence Thomas should recuse himself in all of these cases.

The confluence of cases in the court’s pipeline is extraordinary. It reflects the unprecedented nature of Trump’s autogolpe, or self-coup, in which a country’s leader tries to stay in power through illegal means. Each of the historic cases that is either before the court or likely en route to its chambers represents a different response of the legal system to that core precipitating event.

The justices acknowledged they should recuse themselves from any proceeding where their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

The first of December’s bombshells was special counsel Jack Smith’s request that the Supreme Court expedite consideration of whether Trump has presidential immunity from prosecution. On Friday, the justices declined to step in for now. As we explained earlier this month, there is no absolute immunity and Trump will likely lose this appeal. And with the D.C. Circuit handling the matter on an accelerated basis, it will be back at the Supreme Court in short order.

The next explosive development at the court was its decision to hear arguments in U.S. v. Fisher, which concerns the obstruction of an official proceeding statute under which Trump, and scores of other alleged insurrectionists, were charged. In the worst case, the court could kneecap two of the four charges against Trump in Smith’s election interference case, though that is unlikely.

Now, as if all that were not enough, the 14th Amendment case will certainly make its way to the high court. The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision — finding that Trump committed insurrection and thus is disqualified from the presidential ballot — is clearly right on the facts and on the law. But we recognize that this case will by no means be easy sledding at the court and the timing and outcome are unclear.

Multiple other legal controversies triggered by Trump’s misconduct may be heading the court’s way as well. That almost certainly includes a dispute over whether former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows has the right to remove his Georgia state election prosecution to federal court and Trump‘s First Amendment challenge to the gag order Judge Tanya Chutkan placed on him.

We recognize that the unanimity that characterized important democracy cases of the past — from Brown v. Board of Education to U.S. v. Nixon — is too much to hope for here. But there should be one point of agreement across the high court: Justice Thomas must recuse himself.

Last month, the Supreme Court announced a new code of conduct in response to the still swirling scandals surrounding the institution— in which Thomas featured prominently. As part of this commitment, the justices acknowledged they should recuse themselves from any proceeding where their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” This may arise when a justice has “a personal bias or prejudice concerning a party, or personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts,” knows that their spouse has “any…interest that could be affected substantially by the outcome of the proceeding,” or when their spouse is “likely to be a material witness in the proceeding.”

While Ginni Thomas has defended her behavior in various ways, those justifications don’t matter under the court’s own ethics canon.

Thomas’ involvement in any of the aforementioned democracy cases clearly meets those criteria. As has been exhaustively documented, his wife, Ginni Thomas, was a prominent member of the organization that helped lead the “Stop the Steal” movement that culminated on Jan. 6. She also emailed state legislators in Arizona about creating fake alternate slates of electors and texted Meadows imploring him to help overturn the election results. She attended the rally on Jan. 6 that ultimately devolved into the violent invasion of the Capitol.

While Ginni Thomas has defended her behavior in various ways, those justifications don’t matter under the court’s own ethics canon. The justices must recuse themselves if there is even a question of impartiality “where,” as the canon states, “an unbiased and reasonable person who is aware of all relevant circumstances would doubt that the Justice could fairly discharge his or her duties.” Her involvement in the movement attempting to overthrow the 2020 election is unquestioned — and a rational, unbiased person would reasonably doubt her husband’s impartiality in adjudicating any of these cases.

Moreover, Ginni Thomas’ own personal stake in the cases the court will decide is obvious. For example, she would have an interest in the court finding that the Jan. 6 attack did not qualify as an “insurrection” and that the spread of elections lies — which she participated in — constituted “engaging” in insurrection. And she might even emerge as a witness in some of the proceedings.

Up until now, Thomas has not recused himself from most of the election-overthrow cases where his wife’s involvement should have counseled disqualification. But those cases all came before the court unveiled its new ethics code. Additionally, there is some available precedent to press Thomas to see the light. In October, Thomas recused himself from consideration of an appeal brought by John Eastman. While it is not clear why Thomas recused himself — since the justices are not required to disclose their reasoning — it is likely because Eastman was his former law clerk. Surely his relationship with his wife is even closer than that with a former clerk. In fact, Justice William Rehnquist recused himself from U.S. v Nixon because he had served in the Nixon Department of Justice, a less intimate conflict than being married to someone tangled up in cases before the court.

When it comes to Smith’s request for expedited treatment of the immunity question, we don’t know if Thomas participated or recused himself from the Supreme Court’s decision not to leapfrog the D.C. Circuit. That is because the Court simply issued a one-line order without providing any other information. In our view, Thomas should have stepped away from even this preliminary procedural question.

Unfortunately, the Court’s ethics canon leaves those kinds of decisions to the justices themselves. In violation of the judicial maxim that “no man shall be a judge in his own cause,” it will be up to Thomas to determine whether his recusal is warranted. That means we must temper any hope he will do the right thing. If Thomas does not recuse himself from these cases, no matter how they turn out, he and the Court will be blemished in the annals of history.

[ad_2]

Source link