[ad_1]

Everyone wants to stop opioid overdoses. But it’s unclear how a Republican-backed bill that passed the House last month with Democratic support would help.

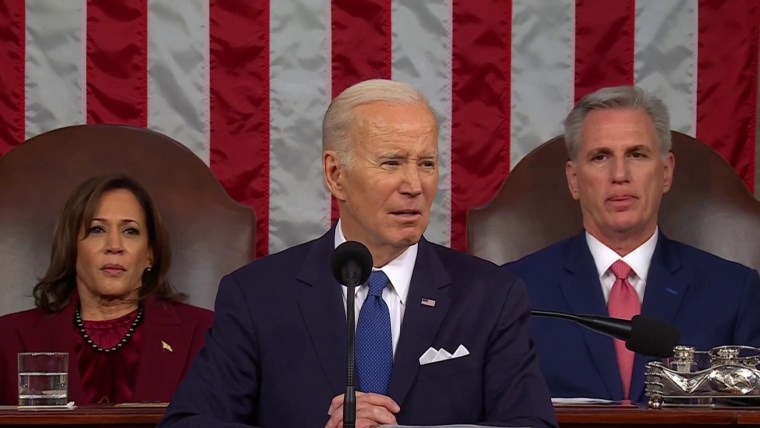

Instead, it seems like the latest chapter in a failed drug war that hasn’t kept people safe. So it’s important to understand what the bill does — and doesn’t do — as the Senate considers it. The Biden administration has supported the measure, which was enacted on a temporary basis during Donald Trump’s presidency.

Called the HALT Fentanyl Act, it would permanently outlaw so-called “fentanyl-related substances” under the most restrictive federal drug control, Schedule I. That schedule contains drugs with no accepted medical use and high potential for abuse, according to the government. Keep in mind: cannabis is also on Schedule I, so the scheduling system isn’t exactly a model of common sense (though President Joe Biden has ordered a review of cannabis’ Schedule I status and it might finally change). Notably, fentanyl itself is used across the country in hospitals for pain relief and is controlled under the less-restrictive Schedule II, which also contains substances with high abuse potential but also approved medical use.

The bill potentially bans substances that not only aren’t harmful, but could even be helpful.

The pending bill wouldn’t change fentanyl’s status; rather, it would permanently place fentanyl-related substances into Schedule I. So what are they? They’re ones with chemical structures related to fentanyl, according to broad scientific criteria laid out in the bill. They’re defined on what’s called a class-wide basis, sweeping in scores of substances instead of outlawing them individually, thus making the government’s job easier on the front end.

The class-wide measure could make sense (relatively, in the context of the drug war) if we knew that all the substances potentially captured by the bill would be harmful. But that’s not necessarily the case. The proposed law, which has been in effect temporarily since 2018, doesn’t require these substances to have similar effects to fentanyl. That matters because two substances being structurally similar doesn’t necessarily mean that their effects are similar. So the bill potentially bans substances that not only aren’t harmful, but could even be helpful, subjecting people to stiff prison terms for benign or beneficial drugs.

More than 150 groups including Human Rights Watch and the Drug Policy Alliance have spoken out against the measure, which they called “a radical departure from drug scheduling practices as it relies exclusively on chemical structure without accounting for pharmacological effect.” They also criticized the imposition of mandatory minimums and Schedule I research restrictions on unknown substances. Nonetheless, 74 Democrats joined 215 Republicans to pass it, 289-133.

And then there’s the question of what good the HALT Fentanyl Act would do even when it comes to potentially harmful substances. As I noted, the bill would make permanent a law that’s been temporarily in effect for several years; it’s currently set to expire next year. Yet, it’s unclear what the outlawing of these substances on a temporary basis has done to mitigate the opioid crisis, such that making the measure permanent would benefit the American people, who’ve continued to die from opioids in the hundreds of thousands.

An exchange over a failed amendment to the bill illustrates the point. The amendment, proposed by Rep. Brittany Pettersen, D-Colo., would have required the Department of Health and Human Services and the attorney general to certify that the act would reduce overdose deaths. After telling a wrenching story about her mother’s addiction, Pettersen said she cared deeply about the issue but that the bill as drafted wasn’t the answer.

Rep. Larry Bucshon, a Republican from Indiana who received an “F” grade from the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, called Pettersen’s amendment a “poison pill” that would somehow let the Biden administration (which, remember, supports permanent class-wide scheduling) “indefinitely delay” such scheduling. The Republican also cited harrowing statistics on overdoses, noting that, in 2021, nearly 108,000 people died of them and 71,000 of those were from synthetic opioids including fentanyl or fentanyl-related substances.

But again — class-wide scheduling was in effect temporarily in 2021 and for years prior. How did it help?

The Senate and Biden should consider that question.

Subscribe to the Deadline: Legal Blog newsletter for weekly updates on the top legal stories, including news from the Supreme Court, the Donald Trump investigations and more.

[ad_2]

Source link