[ad_1]

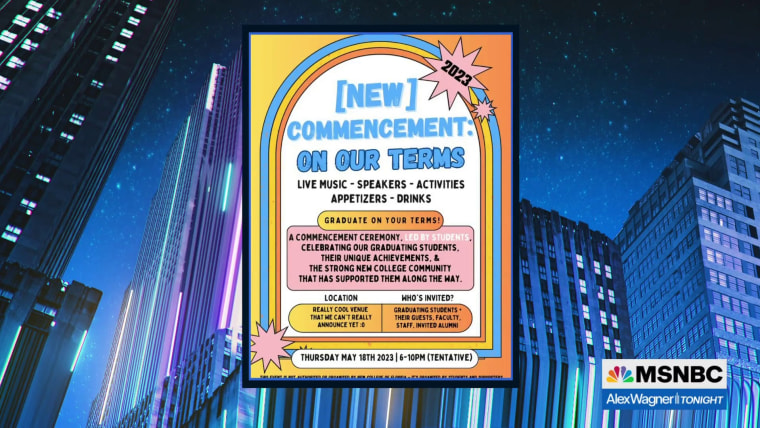

In January, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis appointed six new conservative members to the board of trustees at New College of Florida, including noted anti-critical race theory advocate Christopher Rufo, who’d claimed the public university had been corrupted by “woke nihilism.” The board then ousted the college’s president and made a former Republican Florida House speaker (and DeSantis ally) the interim president. But as The Tampa Bay Times reported on July 18, since those changes at New College, more than a third of the faculty, 36 people total, have departed.

Since those changes at New College, more than a third of the faculty, 36 people total, have departed.

The story about New College was published a day after The Texas Tribune reported that Kathleen O. McElroy, one of the nation’s preeminent professors of journalism and who is currently at the University of Texas-Austin, decided against joining the faculty at Texas A&M University, her alma mater, even after the school held a public event celebrating her being hired.

She said conservative advocates had complained about her past employment with The New York Times and her work to increase diversity in journalism, and she showed The Texas Tribune multiple revisions to her job offer. “This offer letter … really makes it clear that they don’t want me there,” she said. “But in no shape, form or fashion would I give up a tenured position at UT for a one-year contract that emphasizes that you can be let go at any point.”

The fallout from McElroy going public with the way she was disrespected included an announcement from Texas A&M’s interim dean of Arts and Sciences that he’s stepping down from that role at the end of this month and the resignation of M. Katherine Banks, Texas A&M’s president.

“The recent challenges regarding Dr. [Kathleen] McElroy have made it clear to me that I must retire immediately,” she wrote in a letter to the system’s chancellor Thursday. “The negative press is a distraction from the wonderful work being done here.”

Hart Blanton, who leads the school’s journalism and communications department, said in a statement that contrary to Banks’ denials of interfering with McElroy’s hiring process, she “injected herself into the process atypically and early on.” Blanton also said that his signature was added to revised job offers to McElroy without his consent and that he turned over documents to the university’s legal staff the same day Banks resigned.

The exodus of staff at New College of Florida, the refusal of a scholar of McElroy’s stature to come to Texas A&M and the subsequent resignations on that campus are the latest manifestations of the current culture and political clashes over academic freedom and the role of universities in American society.

Even in more ordinary times, leaving a university can be a complex decision that comes with a great deal of internal conflicts over an academic’s obligations to family, career, scholarship and students. The current culture wars roiling universities have further complicated that intense process. Biologist Liz Leininger told The Tampa Bay Times that she began looking for a new position when the new members of the New College board of trustees were announced and committed to leave after the president of the university was fired. She said, “I felt a little guilty to be leaving. I want to support New College students, but I told them, ‘I can support you even from afar.’”

The harm that comes from attacking academic freedom does not end with the faculty.

The harm that comes from attacking academic freedom does not end with the faculty. A college can only function if it has enough instructors who can teach required courses. Without that, the institutions may grind to a halt under increasing class sizes and required courses not being offered. Students can be forced to wait until the courses they need to graduate are offered again or change majors.

This is the situation that New College third-year cognitive sciences major Alaska Miller is in, following the resignation of faculty in the neurosciences department that has resulted in no upper-level classes being offered next semester. She told The Tampa Bay Times, “That means either I don’t graduate on time, or I’d have to abandon my major.”

This is unfair to the students whose matriculation is being delayed through no fault of their own and may drive down university enrollments, which negatively impacts the economy.

In the case of journalism students at Texas A&M, they won’t get to be led by one of the best in the field.

To be clear, so-called progressive faculty aren’t the ones who cherish academic freedom. A “conservative” professor can be assumed to have the same concerns about staying at or coming to a university where their research or teaching may run afoul of whatever the ruling party line is.

As a curriculum theorist, I recognize that these fights are not new. Nor are they that different than the clashes that we see over how race, gender and sexuality should be taught in K-12 schools and the ongoing diversification of curriculum with knowledge from marginalized communities that began in desegregation. The blowback to the diversification of the curriculum has revealed a cultural and political fissure in American society over what universities should teach.

A “conservative” professor can be assumed to have the same concerns about coming to a university where their teaching may run afoul of the party line.

Academic freedom, defined by the American Association of University Professors as “the freedom of a teacher or researcher in higher education to investigate and discuss the issues in his or her academic field, and to teach or publish findings without interference from political figures, boards of trustees, donors, or other entities,” is the intellectual cornerstone of American higher education. It is also currently protected by U.S. Supreme Court precedent in Sweezy v. New Hampshire and Keyishian v. Board of Regents.

Those opposed to academic freedom think the party in control of a state’s government should control what’s taught to teenagers and adults.

It is possible that the New College can replace the third of the faculty that it’s lost, but if it cannot, then that will mean a profound disruption of student learning and knowledge creation.

And, to repeat, attracting new faculty will be difficult because most professors, even conservative ones, will avoid institutions they know are restricting academic freedom. They know that in such places, because of whom it might upset, they may not be able to engage in the research they wish to explore and cover topics relevant to their academic discipline.

This battle in the culture war is part of a larger fight over what knowledge should be taught. It is an overtly political and cultural question that comes with far-reaching consequences for every individual and community involved directly or indirectly in higher education.

Politicians committed to culture wars, such as DeSantis in Florida and Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, can have universities that are spaces where students encounter the full range of intellectual diversity protected by academic freedom, or that are sites of dissemination for political party orthodoxy, regardless of the party in power.

They cannot have both.

[ad_2]

Source link